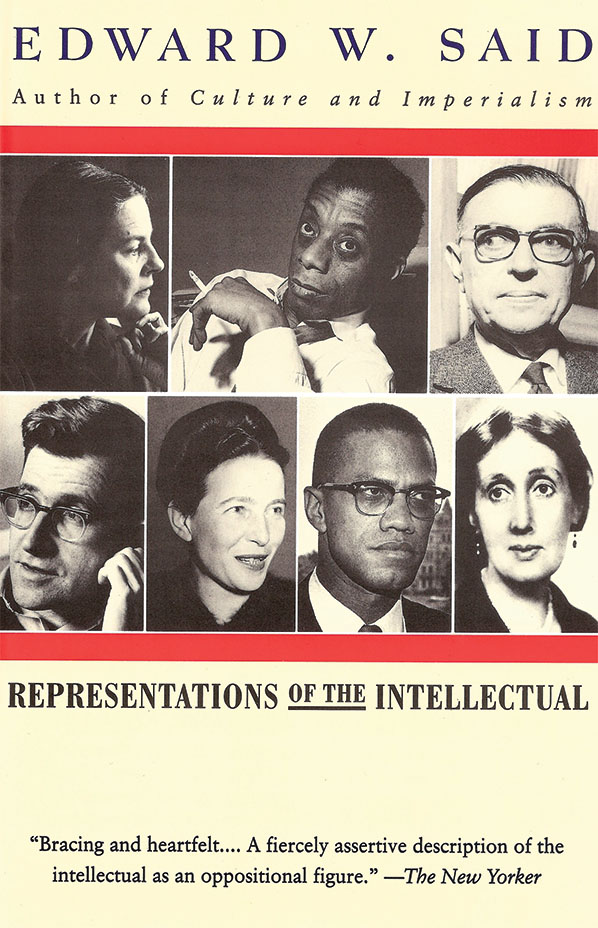

REPRESENTATIONS OF THE INTELLECTUAL

by Edward W. Said

Rosanna van Mierlo

What I want to discuss are four pressures which I believe challenge the intellectual’s ingenuity and will. […] each of them can be countered by what I shall call amateurism, the desire to be moved not by profit or reward but by love for and unquenchable interest in the larger picture, in making connections across lines and barriers, in refusing to be tied down to a specialty, in caring for ideas and values despite the restriction of a profession.

Part of the BBC’s famous Reith Lectures in 1993, Edward W. Said’s introduction to this assembly of his radio essays starts off by recalling how the station’s claim to journalistic truth, objectivity and therefore power was, and is, inherently complicated by its geographical history as ‘the voice of London’. Growing up in the Middle East, there was ‘the assumption that “London” tells the truth.’ Yet ‘how does one speak the truth? What truth? For whom and where?’

Only 121 pages long, Said’s book – although weighed down by that hefty title – has a light touch quality to it, as he skilfully navigates his way through the development of what we call ‘Intellectualism’ with a capital ‘I’ via historical, political, social and personal shifts in the last century. Said’s main claim, that in order to be a ‘real’ intellectual, one must remain an outsider and, as such, embrace a certain degree of amateurism, is not as much new as it is good to be reminded if its urgency.

by Edward W. Said

I read this book as part of my introductory reading list for my Master’s degree in the summer of 2013. At the time most of it failed to capture me as my interests lay with the more glitzy fields of gender studies, poetry and the works of feminist critics like Butler, Cixous and Irigaray. I had little time for the struggles of the Middle Eastern world or the rise of neoliberalism in the West, which is both depressing and exasperating in its inevitability.

Yet reading Said’s work again, four years later and in the throws of developing a career in both the art world and academia, I suddenly realised that this urgency rings true not just for academia but also for the arts. Said’s description of the intellectual as caught in a suffocating net of neoliberalism expressed as professionalism calls to mind Michel Feher’s lectures ‘The Age of Appreciation: Lectures on the Neoliberal Condition’ given at Goldmiths during 2013 – 2015 in which he described the increasing influence of the capital market-model on how we experience our own lives and form our identities. These days, everyone is the manager of his or her own destiny; we are all professionals, motivated by specialisation, expertise, power/authority and funding.

Said describes the problem of the neoliberal condition as strikingly visible in the surge of what we call ‘professionalism’ and its jargon, when he describes a conversation he had with an air force veteran, in charge of bombing during the Vietnam war.

As we chatted, he provided me with a fascinating eerie glimpse into the mentality of the professional […] I shall never forget the shock I received when in responding to my insistent question, “What did you actually do in the air force?” he replied, “Target acquisition.”

The biggest threat to freedom of critical thinking, which I would argue is as important for the academic as it is for the artist, is the increasing validation of professionalism and expertise. These are inevitably connected to systems of power, which in turn are often accompanied by tools of validation and affirmation like funding. The danger in becoming nothing but an expert or a professional is that, in order to sustain that label, we neglect conducting ourselves and our practice freely, meaning solely motivated by our own genuine interests and critical opinion. As Said puts it:

‘The issue is whether [the] audience is there to be satisfied, and hence the client to be happy, or whether it is there to be challenged […]’

In neoliberalism, the ‘client’ relationship does not just exist in the literal sense of the word. It has grown to encompass your manager, the funding bodies that support your practice, the group of other professionals you hang out with. It has gone so far as to even mean you. The contemporary individual embodies both worker and client, constantly working on his or her own brand and targets. Which leaves us at a confusing impasse. How do we satisfy ourselves? How do we remain true to our own desires and interests when we want to be professionals?

Amateurs, Said argues, hold the right to express interest and thus opinion on anything outside their own field, crossbreeding their interests but remaining free of authority of the obligation to speak ‘true’. It is our gateway to radical, lively and original discourse that exists outside of power. It is the origin of the grassroots movement that claims nothing yet discusses everything.

About the author:

An internationally renowned literary and cultural critic, Edward W. Said is University Professor at Columbia University. He is the author of fourteen other books, including Orientalism, which was nominated for the National Book Critics Circle Award, Culture and Imperialism, The Politics of Dispossession, and, most recently, Peace and Its Discontents.

REPRESENTATIONS OF THE INTELLECTUAL

by Edward W. Said

First published in London: Vintage Books, 1994

Rosanna van Mierlo is a contemporary art critic specialising in feminist avant-garde, performance studies and (bio) politics. She is the Book Review Editor at Sluice.

rosannavanmierlo.com

This article was published in the Autumn 2017 edition of the Sluice magazine.