Kathrin Böhm

Company Drinks

Company Drinks is an art project in the shape of a drinks company. It links the history of East Londoners ‘going hop picking’ in Kent to the formation of a new community enterprise, which brings people together to pick, process and produce drinks in east London today. With Company Drinks the commercial supports the communal and cultural.

Each year, Company Drinks run a full drinks production cycle of growing, picking, processing, branding, bottling, trading and reinvesting. They produce syrups, sodas, saps, tonics, ciders, pops and beers. And create an open, inter-generational and cross-cultural public space, where they can meet to produce something useful with and for each other.

Company Drinks began in 2014, with a simple invitation to residents in the London Borough of Barking and Dagenham to go picking again. Since then, more than 36000 people from across the borough and London wide have engaged with the company through harvests, workshops, public events and Hopping Afternoons. Today, Company Drinks have developed into a fully-fledged community enterprise with a permanent base in Barking Park.

Sluice: It seems there’s two ways to approach Company Drinks, one as a company in the marketplace and then as a socially-engaged artwork and platform. So in one way it needs to operate fiscally responsibly and yet it’s also dealing with a completely alternative set of exchange values, do these ever conflict?

Kathrin: It’s very much about this social space we’re creating, and that’s also how we advertise and promote the picking trips, so we’re not saying come and pick for us for eight hours because we need free labour. We’re referring back to this history of people from east London going picking, which a lot of local residents remember, but it’s also a very universal thing so people can see value in this idea of going picking together, and then we make it very clear that this is an invitation, and the deal is that we cover all the costs on the day, and in return we ask everyone to give us half a day of what they’re picking. But of course there’s a weird assumption around the fact that because we have ‘free labour’ our production costs go down which of course is not the case because it’s not a very cost efficient way to take a hundred pensioners to Kent to hand-pick a few hops. The drinks cost a pound per bottle to produce, in Barking where we’re based we sell them for between £1.20 and £1.50, at Frieze we sell them for £3, so there we make a profit, but we’re committed to selling half our stock in the Borough of Barking, because otherwise I think it would be exploitative. Our relationships to the borough would be a bit imperialistic, as in exporting value without sharing the profit.

The idea was always that Company carries two meanings – the fact that a lot of the production is about social space and being in good company and creating this more cultural space. But we’re also Company, less capitalistic but focused around ideas of community economies, so we try and communicate that we produce a lot of different values and we generate a lot of different contributions outside of the purely capitalist.

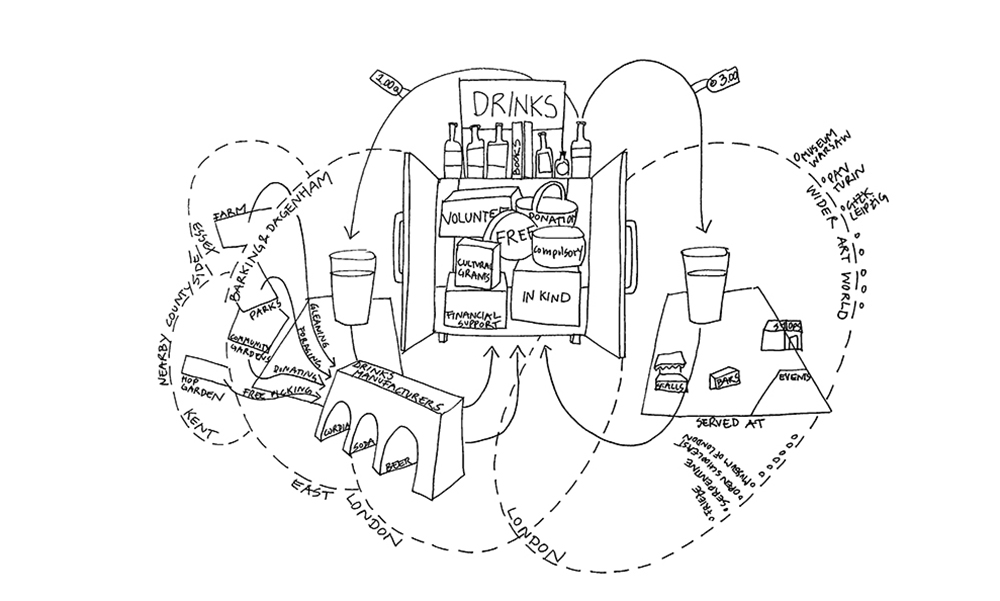

Sluice: We’ve just published an infographic that lays out how Sluice functions financially, which we did as we wanted to increase our operational transparency, but I think much more interesting would be an infographic that attempts to lay out the alternative economy that actually enables us to exist. You have produced a diagram on your website that attempts to map your alternative economy...

Kathrin: Yes, it’s about reclaiming economy as a cultural realm, and just because it’s dominated by capitalist thinking doesn’t mean we can’t engage with it. I think it’s really a reclaiming exercise. We have to constantly remind ourselves how easy it is to become trapped in capitalistic arguing, like I’ve just done with you, I just talked about income, I shouldn’t have done this, the economic geographer Katherine Gibson would have started with all the other values that are being produced, so it’s a constant rewriting, reclaiming. Obviously we’re using and creating many different economies but one big ambition is to stress the fact that the way we deal with each other is the cultural economy. So we have to take control of that, we can’t just leave it to capitalist thinking to tell us what economy is, because what we value and what we exchange even on a small scale is within our control to reclaim.

Sluice:

The problem with reclaiming what constitutes an economy seems to be that non financial valuations are neither clear nor standardised, are subject to uncharted fluctuations and ultimately participants in the exchange may not even be aware of the economies that are being traded...

Kathrin: That’s true, because I think most people think that economy is something that’s being delivered to us by some specialist. I think we need to really communicate this idea that we are all culturing an economy. Everybody recognises a good deal, deals are quite a mutual moment, and I think a lot of the projects I do are about this mutual moment where we have an idea, and for it to work someone has to recognise the value in that, and people take part, and it’s not compulsory. In circumstances where you have two parties where both can make decisions you can have mutual agreement. So if people come and pick in the countryside for free for a day, they get a day in the countryside they don’t have to pay for.

With the Centre for Plausible Economies, because we’re fundamentally an arts project we wanted to bring a certain cultural discussion back into our programme. So in addition to the picking and other communicative strands we wanted to instigate a further art programme with the topic of artist-led economies, taking back the economy and the artistic strategies required to do that.

Sluice:

As we’re operating within a capitalistic system, what can we actually hope to achieve?

Kathrin:

There are different scales, of course, everyone I know who puts effort – including your magazine – into promoting the idea of not-for-profit activities, of course we all hope to overturn the system, which doesn’t look very likely at the moment, so I think then one thing is to network, and also to remind ourselves of the much bigger global network and discussion. So we are looking at different scales, maybe we don’t have a critical mass to overturn things but I think it’s important to keep practicing those ideas even if we don’t have a revolution tomorrow.

Sluice: You recently launched your Centre for Plausible Economies with a talk titled ‘Redrawing the Economy’ which was moderated by Alistair Hudson, Alistair is known for promoting the idea of useful art, is this an area you see Company Drinks occupying?

Kathrin: ‘Useful’ is not a very precise term, because something that is purely aesthetic can also be useful, so I think the term is used mainly as a provocation. I think Tania Bruguera at Arte Útil and Alistair Hudson are now shifting the language a little bit to this idea of user-ship which makes it more practical

as a term to engage with, and it leaves it a little more open to how anyone that engages with it wants to use it. In the case of Company Drinks if someone wants a drink then it can be functional, but if someone wants to exhibit it then that is also fine. So I think that to allow for many different uses as possible is important.

Sluice: The idea of useful art seems to me to be attached to the idea of the arts being instrumentalised to provide services that promote social cohesion. I see this expressed in funding outcome requirements and where artist groups are stepping in and taking over and re-opening libraries as community projects for instance. Do you see a connection between those things? Between the idea that art could be useful and then art having to be useful?

Kathrin: Well of course the Tories idea of ‘Big Society’ as an idea to off-shift all social responsibility to society itself and the government is stepping out, I’d be strongly against that, I think the state has to provide certain welfare structures for the system to work fairly. If we would feel like we were being instrumentalised to deliver things that I think the state should provide we would be very very careful, it hasn’t happened to us yet. It’s happening to colleagues in the library service and then when we see it I think it becomes a matter of solidarity.

Sluice:

Finally, as an artist do you have a studio practice other than your community based work?

Kathrin: No, no, I studied abstract painting, and I still love hard edge abstraction, but I just wasn’t interested in having a gallery audience as my only audience. And also the role of the object in the gallery is just very limiting and I think again if you come back to the idea of user-ship, if you operate outside of the exhibition space there can be a much more dynamic and flexible interaction, so really it had more to do with how I wanted to work with others when it comes to art making.

What I do I do as an artist, but all the work that I initiate or work on is placed within everyday situations. So my work is not studio based towards a gallery context. But it exists within everyday places and cultures. So, the formats I engage with are often very familiar to those everyday structures like a shop or a school or a drinks company. But they are set up as art and they remain art. It’s not important to me if everybody uses them as art or thinks of them as art or sees them as art, but it is definitely their origin and I think over time it becomes obvious to everyone that’s involved that a certain messiness and complexity and playfulness is possible because it’s art.

Company Drinks was set up by Kathrin Böhm in May 2014, with the help of the Create Art Award. Company Drinks registered it as a Community Interest Company in 2015. Today, it’s run by Kathrin, Cam Jarvis, Pip Field, Oribi Davies and Tracky Crombie.

companydrinks.info

This interview was published in the Spring/Summer 2018 issue of the biannual Sluice magazine.